In the midst of these unprecedented times, GLIDE’s Officer and a Mensch program and annual Alabama pilgrimage explore what truly compassionate human interactions and racial justice should look like. These two programs endeavor to address deep systemic inequities through immersive dialogue with history and by developing partnerships and allies among people working inside the criminal justice system and other centers of institutional power.

At the center of these two initiatives is Rabbi Michael Lezak, of GLIDE’s Center for Social Justice, who recently discussed with us the opportunity they present for racial justice through processes of truth and reconciliation.

“It feels to me that the ground is incredibly fertile to grow something, now,” says Rabbi Michael.

“Call it an earthquake, call it the match. The pain has been so deep for so long that the murder of George Floyd was the rupture that created a moment of immeasurable pain and profound opportunity. Broad swathes of America are now waking up to issues that GLIDE has paid attention to for fifty plus years.”

An Officer and a Mensch

GLIDE has historically recognized police as part of our community, who must be working partners in changing the systems we are in. An Officer and a Mensch offers a curriculum that is an extension of this history, one that seeks to instill a greater understanding of care between law enforcement and the people of historically oppressed communities like the Tenderloin. It’s proven popular and encouraging since its inception in 2018 and this fall will move to an online format that, while a necessary adjustment to the reality of an ongoing pandemic, offers the chance to bring even more participants into the program.

“I have been in weekly contact with [program co-founder] University of Oregon Police Chief Matt Carmichael about how we can pivot An Officer and a Mensch to be an online program, and he could not be more excited about this opportunity,” says Michael. “He believes that the police world is ripe for learning like this and is open in a way that they have not been. He believes that pivoting to have this program online will expand both the depth and the reach of this work.”

By way of further evolution of An Officer and a Mensch, the program will now include a community advisory board.

“Three people are signed up thus far,” confirms Michael, including a police captain who joined GLIDE on this year’s Alabama Pilgrimage. “The idea is to explore how to tap people who are on the inner circle of police departments and police reform to help us think about systemic change.”

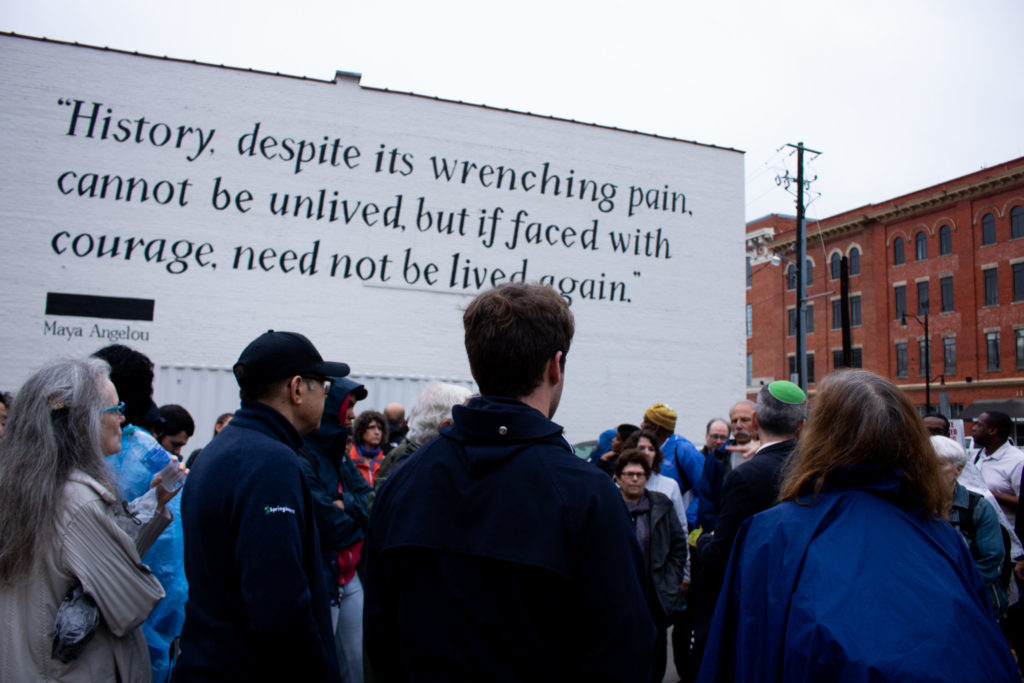

Alabama Pilgrimage: A reckoning with America’s history of racism

Essential to the collective issue of justice and reconciliation is the history of racial injustice in this country. When the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), located in Montgomery, Alabama, opened a Legacy Museum and a National Memorial for Peace and Justice in 2018—precisely to encourage a national conversation about racism and its legacies—GLIDE mounted a group visit to Montgomery to coincide with the openings of these powerful centers of truth and reflection.

This pilgrimage to Alabama has now become an annual undertaking that includes GLIDE staff as well as community members and partners to explore the deep connections between the history of this country and the ongoing challenges we face as a society. The trip follows a series of preparatory courses, organized by Rabbi Michael and Isoke Femi of GLIDE’s Center for Social Justice with support from James Lin, GLIDE’s senior director of mission and spirituality, which are designed to maximize the opportunity for insight, group communication and social transformation among the participants. The group also gathers multiple times after returning, coalescing as a community to harness a continuing collective effort towards justice.

“I describe the Alabama trip as a pilgrimage,” explains Michael, “which I define as a journey of personal, spiritual discovery that forever changes you.

“Isoke and I meet monthly for 90 minutes with the Alabama alumni, which this year includes GLIDE staff and employees of UCSF and San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD), in this Rise and Step class. The purpose is to both help check-in with them spiritually but also process how to become activists on the ground here, to take the fire and energy they got from Alabama and translate that to action here in San Francisco. It is about the connection between spirituality and activism.”

“UCSF is the second biggest economic engine in San Francisco,” explains Michael. “They have 30,000 employees and put $6 billion into the budget and have a history of systemic racism. Until the mid-1960s they had something called The Basement People, which were primarily people of color who cleaned rooms and cooked in the kitchen and janitorial staff who could not eat in the main dining room. They had to eat in the basement. The first African American professor at UCSF is still on faculty. We are agitating with them, using Alabama as a through line, to connect the dots from slavery to mass incarceration to mass poverty but also systemic racism and inequity in healthcare—both in the delivery of healthcare and the education of healthcare systems.

“This is a loving community,” continues Rabbi Michael. “A sweet, loving group of people. Isoke and I meet weekly at a gathering with 25 UCSF senior leaders who were all on the Alabama Pilgrimage with us this year from March 1 through March 5. These 60- to 90-minute gatherings have become a spiritual support group, and a political and strategic planning group to think about how to birth a truth, justice and reconciliation process at UCSF.

“In my wildest dreams of being a Congregational Rabbi, never would I have thought I would be involved in systemic change like this.”

The common denominator is transformation

“I believe in the power of transformative change, not just for an Officer and a Mensch or in Alabama, but when members of the community come into GLIDE’s kitchen to bake challah or to serve meals or hand out clean needles. I see that as a pilgrimage too. Those five days on the ground in Alabama or two hours in the Tenderloin operationalize all of [EJI founding executive director] Bryan Stevenson’s four points: They gift you with proximity; they help you imagine new narratives; they tether you to hope; and they make you willing to do uncomfortable things.

“EJI talks about lynching as racial terrorism. Police violence is racial terrorism. In the most nightmare kind of way. To courageously talk to police officers and district attorneys about this, I think is really important. It is hard but to help them see that they are part of a history that is really terrifying—that is our opportunity with these programs.”

By Erin Gaede