The information below is an excerpt from Glide’s Historic Building Request

A photo of Cecil as a baby

Albert Cecil Williams was born in San Angelo, Texas on September 22, 1929, to Sylvia Lizzie Best and Cuney Earl Williams. The Williams lived in the home owned by Sylvia’s parents, Jack and Phyllis Best, at 201 W. 8th Street, in the “black section” of San Angelo. You can learn more about Cecil’s childhood in the film Coming Home (Part 1 – Part 2 – Part 3 – Part 4 – Part 5 – Part 6) Jack Best, known as “Papa Jack” to the Williams children, was a former slave who moved to the Southwest to work as a cowboy. Phyllis Best, known as Lizzie, was half American Indian.

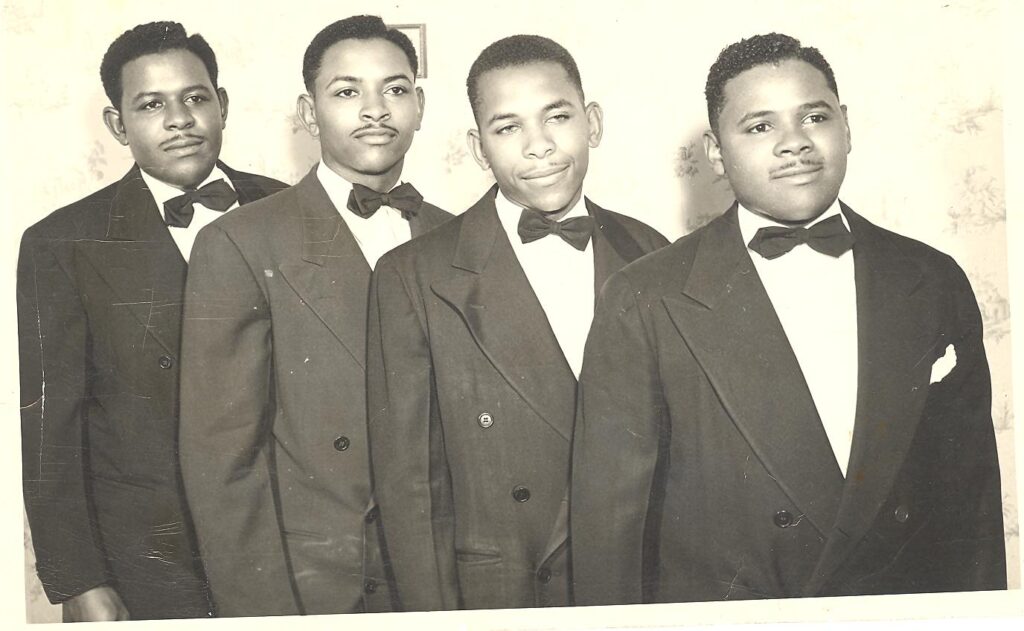

Earl, Cecil, Claudius, and Jack Williams

Cecil was the second youngest of six children: Johnnie Mae, Earl Jr., Arthur J., Claudius Maurice, and Rudy E. Cecil’s childhood nickname was “Rev,” short for Reverend.

“Like many black families whose options seemed beyond their control,” the Williams family attended church every other day of the week. Wesley Methodist Church, according to Williams, “provided a frame of reference, a safe meeting place, and a context in which to view our lives.”

Growing up black in Texas in the 1930s was difficult and at times excruciatingly painful. “Blacks were niggers in substance even if we were ‘Nigra’ or ‘colored’ in name,” writes Cecil.“There were three kinds of public restrooms in those days; ‘Men,’ ‘Women,’ and ‘Colored.’” The railroad tracks marked the unofficial boundary between the black section of town to the north and the white community and business district to the south. Williams referred to the dirt path along the tracks as Freedom Path: “When we emerged from the white community and set foot on Freedom Path, we knew we’d made it once again. No harm would come to us there.”

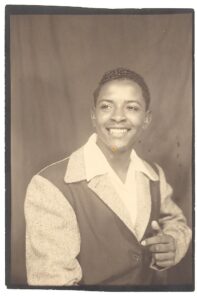

Cecil at age 16

Cecil Williams was a successful student, serving as class president each year of elementary and high school. “If only within the framework of young black children growing up in dust-blown West Texas, I was already a leader. Many of the adults, including Mother most of all, indicated with their praise that somehow I would escape the boundaries of San Angelo and clear the barriers that restricted our community.”126 He attended the all-black Sam Huston College in Austin, Texas, where he served each year as class president. During summers he worked as a janitor at First Methodist Church of San Angelo, where his father worked for many years as a janitor. Williams says of First Methodist: “whose all-white congregation was Christian enough to pay blacks as janitors even if we were not permitted to pray there.”

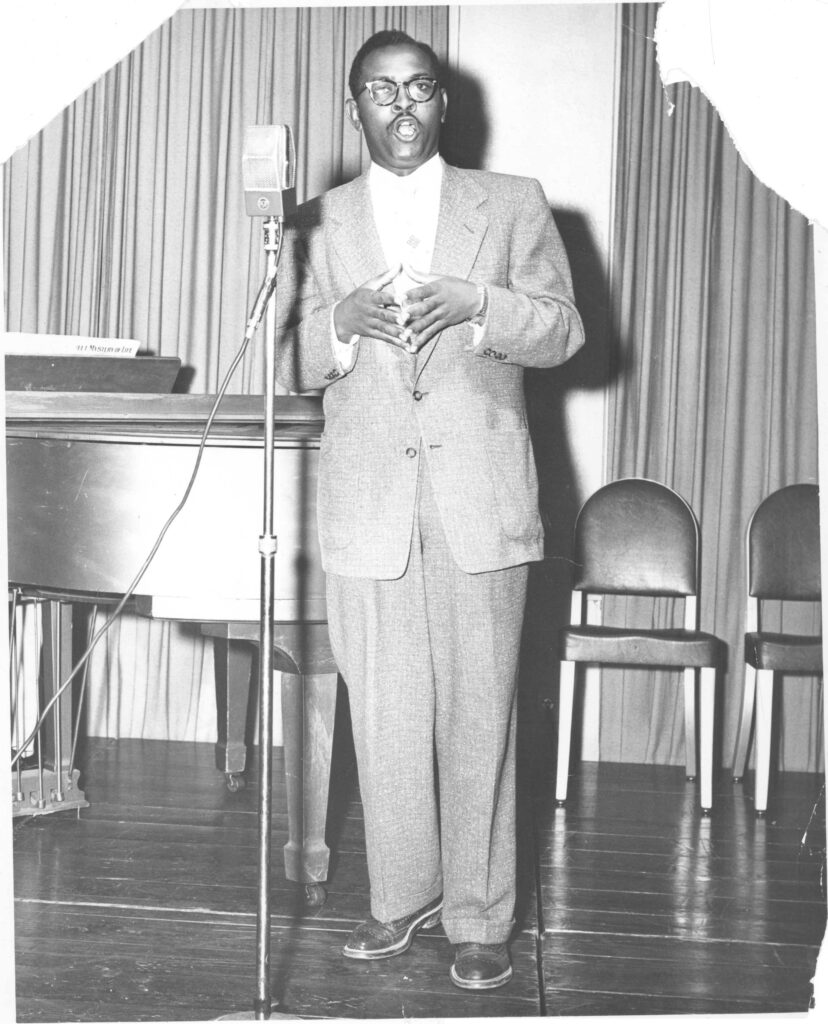

Prior to his time at Glide Memorial Church, Cecil was known throughout the South as a gospel singer. He travelled to churches singing with his brothers. Often facing discrimination, the group had to enter many worship spaces through the kitchen.

By the age of 19, Williams had obtained his Exhorter’s License, the first step toward a career in religion. “I was going to become a minister, the best they ever saw. Step by step. Four years of college, then seminary, then an appointment to a large black church in a big city like Dallas.”

At Sam Huston College, Williams met J. Leonard Farmer, the first black to earn a Ph.D. in Texas.130 Leonard almost instantly became a mentor to Williams, who describes Leonard as “an eccentric who defied traditional order by creating a chaos of his own…. He shocked me. He said that [Jesus’s] legacy was one of radical, earthly action rather than heavenly, spiritual peace. He raised questions about the biblical text and railed against the presumed order of theology. He injected chaos into theology and my life…. He was a walking revolt who ran so deep that part of me wanted to be just like him…. J. Leonard Farmer had given me a sense of pride and confidence. But more than that he’d shown me that one could defy order and still survive.”

After graduating from Sam Huston College with a B.A. in Sociology 1952, Cecil Williams attended the Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University in Dallas for three years. He was one of five black students admitted that year, a small group chosen to integrate the seminary. Williams was a rising star at Perkins. A few black ministers in the Methodist Church called him their “son in the ministry.” “They never tired of predicting great things for me. I was their choice, the one to carry forth the great tradition on which their own lives and careers rested.”

He worked as a student pastor in the church of I.B. Loud, one of the most powerful black ministers in Dallas. Loud often let the student pastors preach. Taking a cue from his mentor J. Leonard Farmer, it was in these early sermons that Cecil Williams began to revolt against racism in the church. Williams includes an example in his autobiography:

Look at a church that rejects people based on color…. We’re all black, aren’t we? Try to go into a white church…. They won’t let us in. They’ve never let us in. They’ve never let us in…. Now we must ask ourselves: What kind of Christianity is that? I say to you right here and right now that the church must change its racist policies if it is to be what it says it is. Not somewhere else. Not some other time. Right here! Now!

As a graduate of Southern Methodist University, Williams writes that his secret dream was to become “the first black minister named to pastor a white church in Texas. Still longing for acceptance. Still yearning to make it. Knowing I never would be accepted in the white church, white world.” At the same time, he felt that he could never be “what the black ministers wanted [him] to be.” In other words: tolerated, but not accepted, by the white church. “That was their idea of making it.”

Cecil Williams’ first appointment as a minister, in 1956, was to Hobbs, New Mexico. He was appointed to Hobbs by the black bishop of the West Texas Conference of the Central Jurisdiction of the United Methodist Church. He soon found out that he was sent to Hobbs to create a Methodist Church for the small black community who had started attending the white Methodist Church. According to Williams, he was “imported” to Hobbs to “relieve the white church of any racial embarrassment.” While living in Hobbs, Williams married a school teacher named Evelyn Robinson. They remained in Hobbs for a year before being offered the job of instructor and Dean of Men at Sam Huston College, which had merged with Tillotson College and became Huston-Tillotson.

From 1956 to 1959 he taught and served as chaplain at Huston-Tillotson College. Soon into his tenure there, Williams heard that he would be appointed minister of Wesley Methodist Church in Austin, a “real plum” opportunity.139 However, when the decision came to a vote, astonishingly the black ministers in the conference blocked the appointment. Williams’ took this to mean that the black ministers were saying, “You ain’t learned your lesson yet, boy.”

Williams left Texas in a “storm of tears. Soothing and violent. Tears of hurt, rate, joy, loneliness, fear.”

Beginning in 1959, Williams began graduate work in sociology at the University of Texas, Austin, and also studied social ethics and pastoral psychology at the Pacific School of Religion in Berkeley, California.

Around 1960, Williams moved to Kansas City, Missouri, where he served as minister of the St. James Methodist Church. While there, he was finally able to pastor a congregation that included both races.

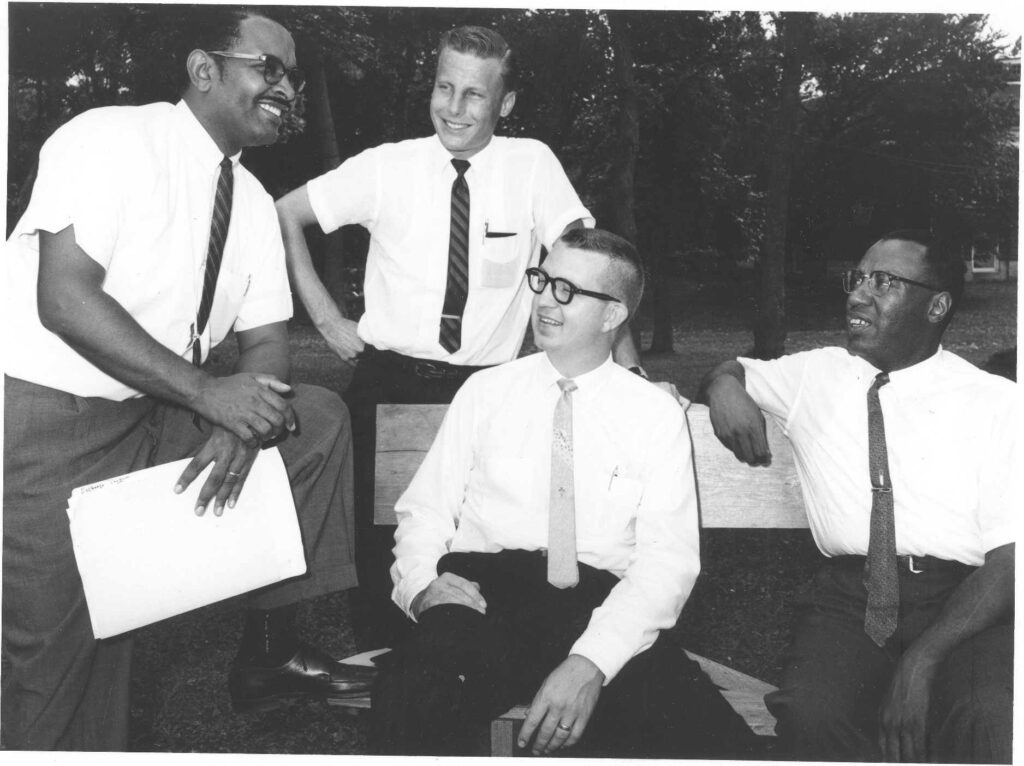

Cecil in Kansas City in 1962, when he participated in a church exchange between black and white clergy.

In 1963, he was minister at a church in Kansas City, Missouri when he was offered the position of director of community involvement at the Glide Urban Center at Glide Memorial United Methodist Church in San Francisco.

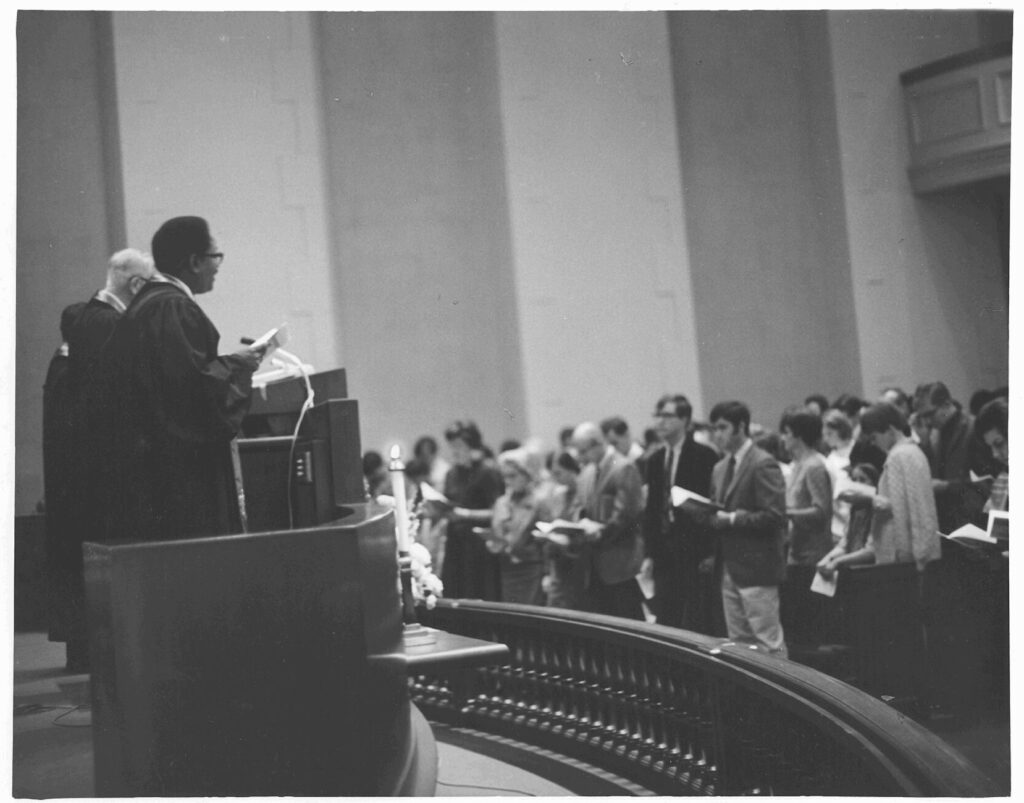

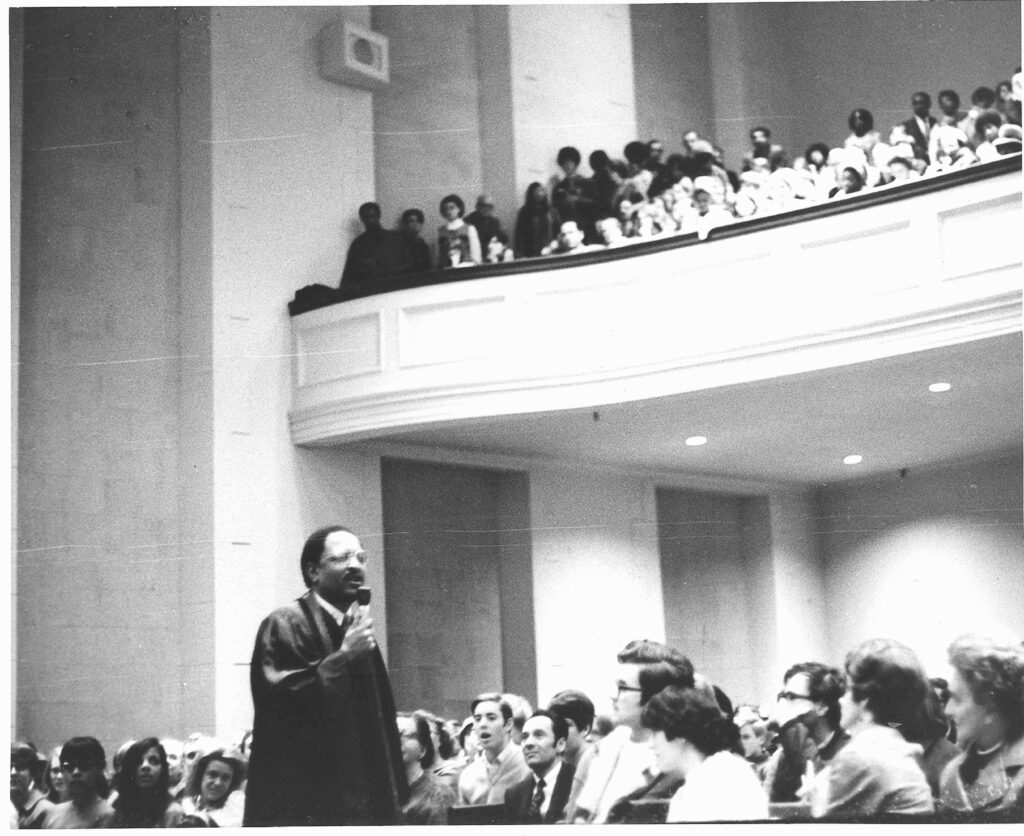

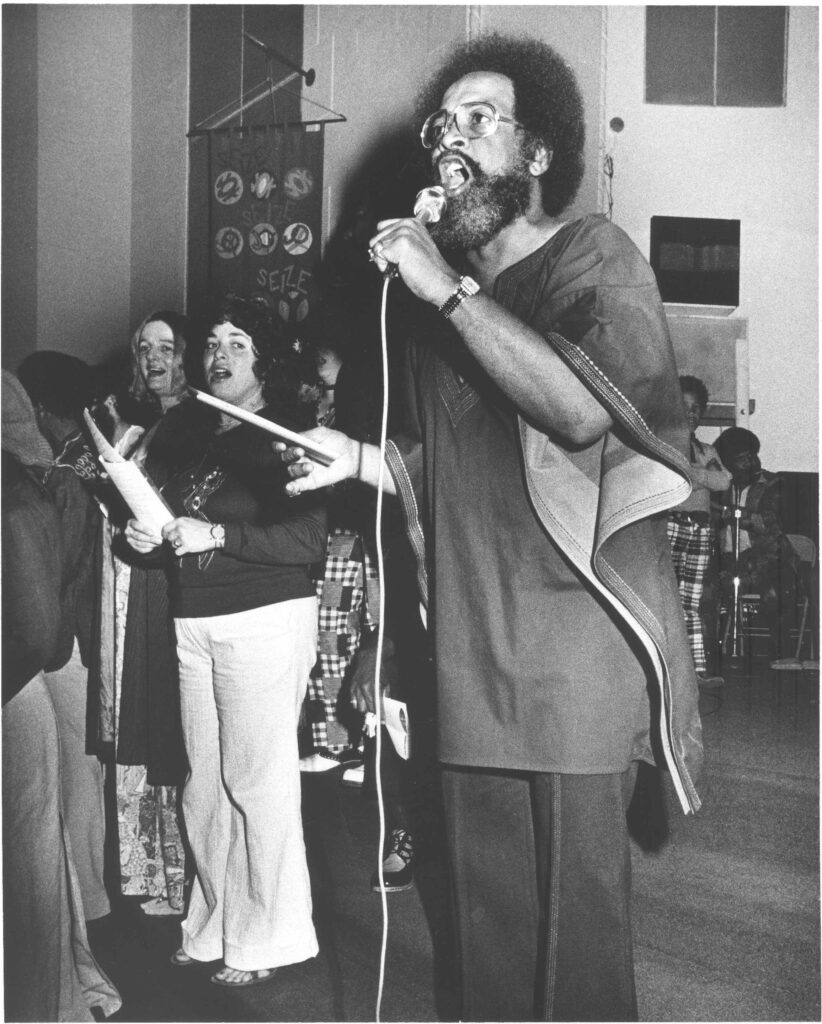

Rev. Cecil Williams in worship at Glide Memorial Church in 1968.

Rev. Cecil Williams describes the Tenderloin when he first arrived at Glide in 1964:

People called the Tenderloin District in San Francisco “the last circle of hell,” because no matter how quickly you drove through it, you couldn’t help seeing the poor, the addicted, the sick, the homeless, and the mentally ill, many of them lying if not dying in the streets. You couldn’t look away from wildly dressed sex workers of all genders (there were more than two) getting clubbed by the police. You’d see flophouses, whorehouses, drug and porno houses, runaway teenagers selling their bodies, cruising johns, and ex-cons. By reputation, the Tenderloin was a filthy, seedy, crime-ridden hellhole that nobody wanted to visit.

Yet the first time I walked through the Tenderloin on my way to Glide Memorial Church … I saw something else, too. I saw the most blessed place on earth.

Whereas others had turned a blind eye to the Tenderloin’s “urban ghetto,” Williams saw something “raw and energetic [rising] up from the streets….: so many poor people—old and young; gay and straight; native and foreign—making a life in wretched surroundings.”

The contrast between William’s description of the Tenderloin and the Glide Memorial Church he was soon to minister was extreme:

I had just left the smell of urine and grime in the streets. Here an aroma of pine-scented furniture polish filled the air…. I couldn’t believe how spotless everything was. The interior of Glide had the hushed and elegant atmosphere of a wealthy men’s club. Hardwood floors gleamed brightly as if they had never been scuffed.

Williams also noticed that every door in the church remained locked and that the windows were barred.

In 1964, Glide’s congregation had dwindled down to 35 people—all white and mostly elderly. Bishop Donald Tippett warned Williams that the remaining congregants loved the church but they hated what the Tenderloin had become: “Keeping the church pristine and ceremonious means a lot to them.” Williams’ response was a rhetorical question: “Did a beleaguered church, a dying church, have to lock out the community to preserve itself?” Williams wanted to throw open the doors and “welcome people with unconditional love…a love that included all.”

“Bishop, there’s one thing you should know,” Williams told Tippett.150 “If I become minister here, I’m going to turn this church upside down.” Tippett replied: “Brother Cecil, welcome to Glide Memorial.”

Glide’s 35 remaining congregants stubbornly resisted change and made Williams’ early experiences at the church frustrating and painful. He endured anonymous racist messages left with the church’s receptionist (e.g., “[T]ell that nigger to go home”), and overheard racists jokes told by his own colleagues.151 The congregants repeatedly walked out of his sermons and twice demanded to Bishop Tippett that Glide replace the radical, new reverend. Ultimately, all but about two of the original 35 members left the church, but Williams remained undeterred.

I was young and enthusiastic, and the early 1960s were already showing signs of great change and promise. I did not expect the congregants to join me in my dedication to serving the poor and disenfranchised. I did hope they would be intrigued enough to discover a new kind of spirituality through diversity…. Whereas Glide had been a “Sunday Church” before without much community involvement, soon it would be a church of action, of movement, of declaration, of confrontation.

The “new Glide,” ministered by Rev. Williams, “was not going to shut out the world.”

Cecil Williams radically transformed Glide in the 1960s, and Glide transformed Williams. He replaced his clerical collar and robe with an African dashiki and “dazzling red pants,” remarking: “Just as I am removing this symbol of traditional clergy, so may we all welcome the time of openness and change that is coming to Glide.” He grew his short-cropped hair into an “afro.”

Cecil Williams 1982

Williams’ changes to Glide’s sanctuary and Sunday morning services were equally radical. He stripped the sanctuary of everything he thought represented traditional church hierarchy: the pulpit, the chancel, the altar, the ministers’ chairs, the choir, and—most controversially—the cross. Williams felt that the enormous, white cross on the wall behind the altar wasn’t serving the people. To him, the cross “wasn’t just a symbol of oppression—it was the oppression. Instead of standing for the unconditional love that Jesus brought to a new community, the cross made people guilty because Jesus died for our sins.” Williams asked the Glide congregation to see and feel the power of God/the spirit within them. Asked by theologians over the years if taking down the cross was his attempt to secede from the United Methodist Church, Williams answer has always been “emphatically no.”

After Williams’ changes to the sanctuary, all that was left of the front of the church was a blank wall where the cross once hung and a carpeted stage. The sidewalls and balcony railing were decorated with banners highlighting the “values Glide stood for”: Justice, Peace, Freedom, Righteousness, Trust, and Community.

Cecil William’s Sunday morning services evolved into a powerful phantasmagoria of spirituality, music, dance, art, and community. He called the services (and they continue to be called) “Celebrations.” The Glide Ensemble replaced the old choir with its repertoire of traditional hymns.

Gone were the dirge-like hymnals; in was the joyous, explosive gospel music of the black church alongside the rich traditions of jazz, rock, folk, and blues…. This music [was] steeped in protest and visions of a more just and loving world…. [and has] sung out against Apartheid, domestic violence, economic and social injustice, poverty and hunger.

Glide Church light show during Celebration. Photograph by Bob Fitch, Courtesy of the Stanford Libraries Archive

Williams’ longtime collaborator and wife since 1982, Janice Mirikitani, introduced a theater group and dance troupe to the Celebrations. Comprised of Glide community members, the groups performed choreographed pieces with powerful socio-political messages. Mirikitani was also responsible for introducing the famous Celebration light shows. After the cross was removed from behind the altar, Mirikitani had the idea to fill the enormous blank wall with images of community—replacing the cross, as Williams had hoped, with a community filled with the spirit. She invited a group of young Asian American photographers called the Red Lantern to take photographs of San Francisco street scenes that would be projected on the wall. Williams writes: “If you were addicted or recently out of jail or chronically poor or homeless, and you thought…that nobody cared, seeing images of people like yourself living from one moment to the next could be profoundly moving.” This was so crucial to Williams’ ministerial goals; he worked tirelessly to make disenfranchised people of the Tenderloin find a home in Glide. “I felt their unvarnished experience carried more honesty and more weight than any of the homilies the church instructed its ministers to present.”

The light shows morphed into a powerful display of news clippings, sermons, songs, poetry, art—often mixed with strobe lights and collages of flowing lava and psychedelic kaleidoscopes. “You couldn’t look at that wall without feeling the vitality of the streets and the exuberance of political confrontation in one giant, ever-moving art installation,” Williams writes.

Mirikitani also worked with Williams to change the format of Celebration bulletins from a “clutter of religious sayings” that nobody read to “provocative modern poetry” and lyrics of “rebellious show tunes” such as “Hair.”

After losing the 35 members Williams encountered on his first day, the Glide congregation was somewhat slow to grow. By 1966, Janice Mirikitani recalls that only about a third of the pews were filled. However, the congregation that existed then prefigured the Glide that exists today. Sex workers and runaway gay teenagers were among Williams’ earliest devotees. As a young, gay man excitedly told Mirikitani: “The uptight people are leaving, and Cecil’s told everybody in the Tenderloin they’re welcome. And nobody’s ever let us in church before.”In the late 1960s and early 1970s, a Sunday Celebration could include:

Hippies in thrift store finery, jazz aficionados, prostitutes, immigrants, drag queens, refugees, homeless people from the shelters, Vietnam veterans, performers from the Mitchell Brothers (the city’s biggest porno theater), revolutionaries in army-navy gear, and…traditional churchgoers in their Sunday best.

Financial Support:

The Rev. Cecil Williams taught us to use our voice to radically welcome others. We continue to proclaim that radical welcome in all that we do! We celebrate the Rev. Cecil’s birthday throughout the month of September. If you would like to help us celebrate, please send a love offering in honor of his birthday. Your support helps us share unconditional love in the Tenderloin, in San Francisco and throughout the world. Contribute to our fundraiser in Honor of Cecil’s 94th Birthday here.