by Hilary Disch

At the time I was arrested I had no idea it would turn into this. It was just a day like any other day. The only thing that made it significant was that the masses of the people joined in.”

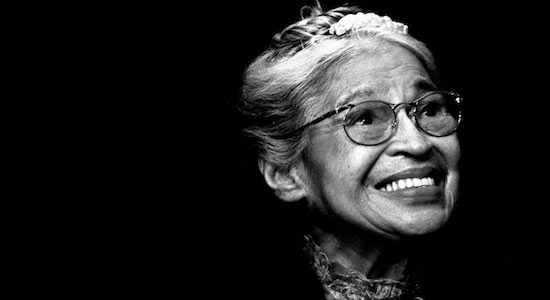

— Rosa Parks

In retrospect, I realize that Rosa Parks was usually allocated a singular page in my elementary school textbooks, perhaps just mentioned in one of the pastel-shaded boxes that checkered the margins. In this fashion, Parks, like many other history-making people of color, was bracketed within the primary narrative of our national history.

Too often, our larger-than-life historical figures, such as Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr., are removed from the movements that they helped to build, their images polished to better fit the type of societal and cultural progression that we like to imagine for our nation. Our heroes are scrubbed of any aspects of their identities that mainstream society deems too radical, too militant, or too leftist. Parks’ New York Times obituary recalled that she once “expressed fear that since the birthday of Dr. King became a national holiday, his image was being watered down and he was being depicted as merely a ‘dreamer.’

“‘As I remember him, he was more than a dreamer,’ Mrs. Parks said. ‘He was an activist who believed in acting as well as speaking out against oppression.’”

Similarly, Rosa Parks herself is often depicted in mainstream culture as an average woman who one random December day did a very non-average thing by refusing to stand up, sparking the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

In reality, Parks was not average or apolitical, nor did she act alone and untethered to a larger movement. Before December 1, 1955, and her ensuing ascent to national prominence, Parks was already well ensconced in the Civil Rights Movement; indeed, she had taken up the fight for equality long before that fateful confrontation on the bus.

In 1943, Parks joined the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP as secretary, and she and her husband assisted in voting registration outreach. Meanwhile, she also attended local meetings of the Communist Party, although she never registered as a member.

In her capacity as NAACP secretary, Parks went on to be the lead investigator in a case involving the horrific kidnapping and gang-rape of a black woman, Recy Taylor, by six white men. Parks and Taylor co-founded The Committee for Equal Justice for the Rights of Mrs. Recy Taylor, which gained a great deal of media attention and the support of well-known progressive figures of the time, including E.D. Nixon, W.E.B. DuBois, Mary Church Terrell, Langston Hughes, Lillian Smith, and Oscar Hammerstein II, among others.

And in the summer of 1955, just a few months before she defied segregation laws on that Montgomery bus, Parks attended the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, an activism education center focused on workers’ rights and racial equality.

Rosa Parks, then, was a trained, experienced activist and organizer by the time of her arrest. However, it was not she alone who sparked the Bus Boycott that fanned the larger Civil Rights Movement. A coalition made up of local academics, the Women’s Political Council and the NAACP was already poised for mass protest. Her brave and defiant action was backed, amplified and immortalized by a larger movement.

This is worth remembering. Very often our heroes—although heroes they certainly may be—do not and cannot make history without the solidarity of an organized movement. When we remove high-profile activists from their historical contexts, political views and ethical frameworks, we risk distorting the individual as well as the movement they fought for.

And we risk something more, something even more damaging to the future of social justice in this country. When we sanitize and glorify our heroes for popular consumption, we risk putting them beyond us, and thus putting the idea of transformative activism out of our own reach.

The truth is we do not need to be famous, wealthy, saintly or Ivy League-educated to do effective work, to lift our voices, to stand up (or sit down, as the case may be) for justice. You can continue the work of Rosa Parks in your school through student organizations, by writing an op-ed to your local newspaper, by asking your immigrant or Muslim friends and neighbors what kind of support you can offer them.

This is the work we do at Glide, where decades of history meet the activism and moral courage of heroes every day—even if you don’t necessarily know their names.