The Stories That We Were Told

A Reflection

By Lilian Mark, Senior Director of Programs at GLIDE

During AAPI (American and Pacific Islander) Heritage Month, I celebrate all of us – the richness of our immigration history, our diaspora, our delicious foods, our beautiful languages, our songs and movements, and the history we will make from where we stand and the people we are able to bring along with us because of our stories, our truths, and our connectedness to one another.

I came to GLIDE in 2004 as an undergraduate intern with a curiosity, a desire, and an eagerness to learn, to be a part of, and to contribute to social justice work. I did not expect or know how much it would do for me. My heart opened big…noticeably big…and not just to the people and the things happening around me in the Tenderloin, but it opened me up to myself.

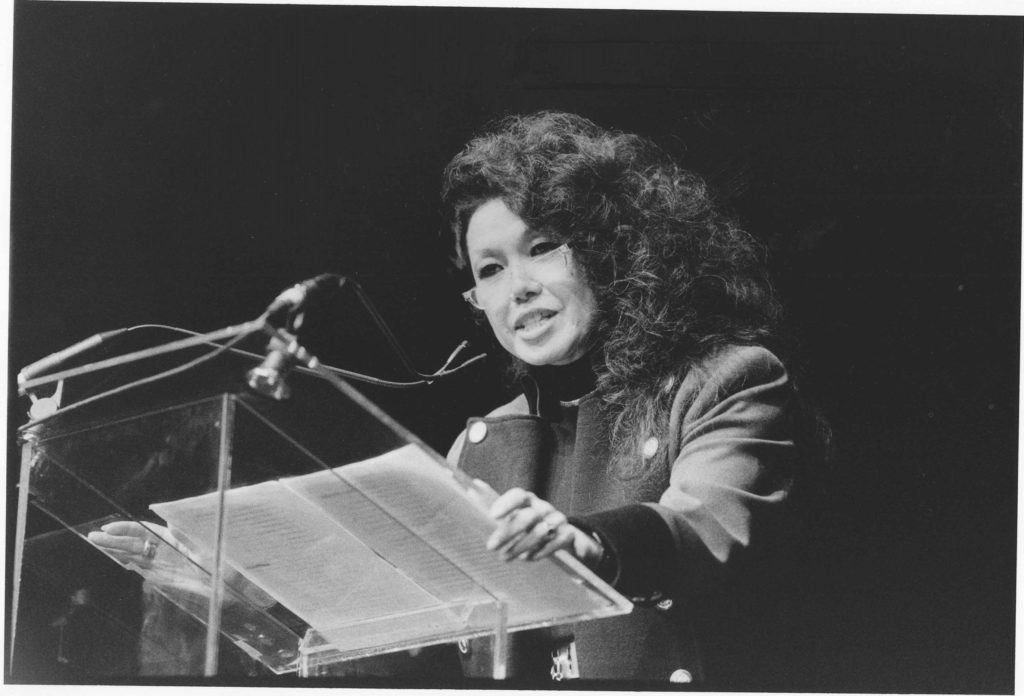

I don’t remember if I knew about Janice Mirikitani, GLIDE’s co-founder, before I arrived, but I do remember the first time I met her and the many moments that we shared after that. Jan walked through the world in her fullness – her pain, celebration, joy, despair, love, and hope. My conscious and unconscious stereotypes, biases, and perceptions about AAPI women at 19 years old were challenged by her. Jan’s accomplishments, strength, vitality, courage, and tenderness did not fit any box I had for AAPI women – and where did I get these boxes? Were they given to me? Inherited? And do I create and/or recreate on my own?

In her life’s work and in the 17 years that I knew her, Jan told her story. Her whole story. In GLIDE’s history of work, Jan’s willingness to be vulnerable and to feel her own feelings invited others to do the same. At GLIDE, we say we are all in Recovery – recovering from being human, from life, and from our individual and collective experiences. Storytelling is one way of healing, particularly for communities of color and marginalized communities where our identities and existence are constantly challenged. We are told we do not belong. We are not allowed to belong. Storytelling helps us to see how we share in sameness, how we are connected, and how we fit in. As with most minority groups, Jan’s story was not just her own. Her story is etched (literally) in Japanese American history in books, on monuments, in museums. Her story represents AAPI women who write, who poet, who dance, who art, who march, who overcome, who fight for justice. Jan taught me, showed me, led me to do my own work – to find my own voice, to understand my own history, to know who I am even if it takes a lifetime to learn it.

The completeness and cohesiveness of my family’s history as Chinese immigrants in America have many missing pieces. The missing pieces usually are not discovered until someone passes away and they reveal themselves as sentiments of the person’s past. I did not know that my father’s uncle was a “paper son” until he passed away. The “paper son and paper daughter” system was a way for Chinese immigrants to come to the United States illegally by purchasing identification documents to bypass the Chinese Exclusion Act. I did not know he attended UC Berkeley (my alma mater) briefly until his studies were interrupted by World War II. He picked fruit in Central Valley and eventually raised his family while running a liquor store in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. It was not until I was 30 years old, that this piece of family history finally helped me make sense of the confusion I had always experienced as a 7-year-old as to why there was this one much older Chinese relative who spoke perfect English – a phenomenon that did not exist elsewhere in my family. This story is not mine, and at the same time, it is mine. It may also be yours. I have always wondered what kind of difference it would have made if I had known more about my family history growing up.

My search for my identity is a constant one. My proximity to my Chinese cultural heritage remains strong through my parents, my family, and my community, but in my daily life, I am enveloped by American, White culture. This experience of understanding, reconciling, and creating my own identity – who I am and whom I want to be as a Chinese American woman persists – the back and forth, the negotiations, the search for integration, the moments of reconciliation, the feelings of loss, and the gratitude for what is.

In my pursuit of my own story, I’ve learned this – there is the story that you are told, the story that you believe, and the story that you repeat. In my 20’s and 30’s, I spent a lot of time uncovering, learning, and understanding the stories and messages that were told to me about me – from parents, family, teachers, media, colleagues, strangers, world. Eventually, these stories meld with my own, the one that I am trying to create for myself, and every day I must decipher who is telling the story today and do I believe it. Am I strong enough? Am I meek? Meek like the stereotype for AAPI women and AAPI women in leadership roles? Am I enough, and do I believe that I am enough? What does enough look like? As I head into my 40s, I now must decide what the story is that I am going to repeat.

As a second-generation Chinese American woman who is also a parent to a young daughter, I feel the responsibility of this even more. I am careful, mindful, and whenever I am not too tired, I try to be intentional about the story I am repeating – about what it means to be Chinese American. For all the moments in my childhood when I had grimaced and felt embarrassed by my parents speaking Cantonese too loudly in public, I seek reconciliation in speaking only Cantonese to her and telling her that it is a gift to be able to speak more than one language. I call her only by her Chinese name because it is also a call out to our heritage. More than anything else, I hope that the story I believe about myself as a Chinese American woman and the story that I am repeating to her is one of love, joy, hope, and resilience.